How to Repurpose EV-batteries

Authors: Noman Shabbir, PhD, Research Fellow and Jelizaveta Krenjova-Cepilova, PhD, Researcher & Project Manager, FinEst Centre for Smart Cities

The TREASoURcE project studies the possibilities for the use of second-life battery packs for energy storage in other applications to avoid recycling the batteries back to the original elements with significant material losses in the process.

In Estonia, interest in second-life battery applications is emerging alongside broader discussions on energy security, renewable integration, and circular economy strategies. However, the regulatory landscape remains fragmented and ambiguous, particularly concerning the safety and classification of used batteries, roles and responsibilities of stakeholders, and the harmonization of practices with European Union (EU) directives, regulations and best practices. Following overview is the short extract from the Project Brief that can be accessed and downloaded in full-length here.

Read more about the use case:

The Most Important Requirements for Success

Develop a National Regulatory Framework

A national task force or working group should be established—including ministries, the Rescue Board, the Consumer Protection Board, the Environment Agency, and technical universities.

Establish Testing and Refurbishment Capacity

Public investment or PPP models should be explored to develop national battery testing labs which could support battery diagnostics, SoH evaluation, and fire safety testing.

Improve the Awareness

Legal Frameworks on Producer Responsibility and Ownership Transfers should be well communicated to different stakeholders, especially those dealing with second-life batteries and working in the repurposing business.

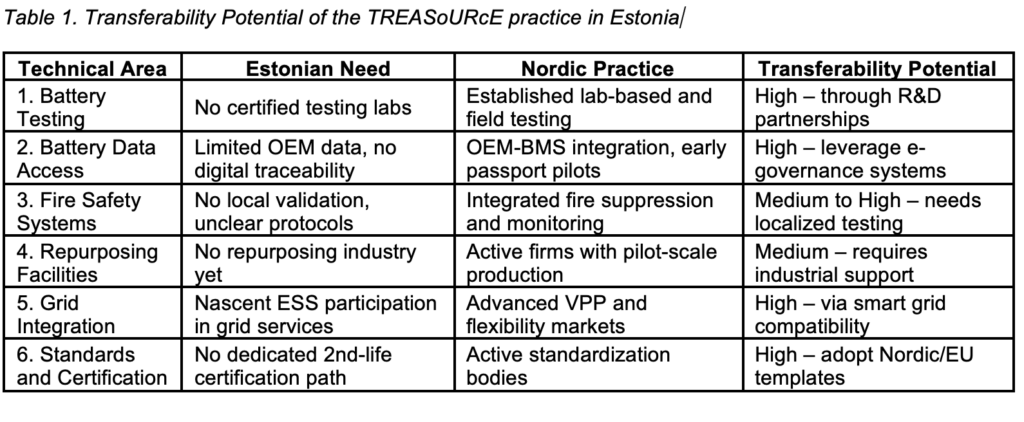

Technical Needs and Possibilities in Estonia

Table 1 provides an overview of technical needs and possibilities in Estonia when it comes to the potential of repurposing second-life EV batteries. These form the basis for the recommendations on adaptation of these practices. Each technical area is provided with the evaluation of the respective needs in Estonia and the relevant practice in the Nordics (i.e. Sweden and Norway). The final column presents the level of transferability potential on a scale from high to low potential.

Battery Testing Infrastructure

In Estonia, a key technical barrier is the absence of certified and standardized testing facilities for used EV batteries, especially for assessing battery state-of-health (SoH), degradation, and safety risks. In countries like Norway and Sweden, companies and research institutions have established battery testing protocols and laboratories to evaluate the safety and performance of second-life batteries (e.g., RISE[1] in Sweden, IFE[2], SINTEF and ECO STOR[3] in Norway). There is potential to establish modular or mobile testing units at TalTech or other R&D institutions. Knowledge and protocols from Nordic labs could be transferred through joint research programs or bilateral cooperation, enabling Estonia to leapfrog into standardized testing.

Battery Data Access and Traceability

Estonian stakeholders lack reliable access to battery history data (e.g., SoH, charging cycles, user history), which is essential for safe reuse and repurposing. Nordic actors are moving toward Battery Passports and OEM collaborations for data sharing under GDPR-compliant frameworks. Norwegian second-life companies often obtain direct access to vehicle battery management system (BMS) data. Estonia, known for its strong digital infrastructure and e-governance systems, could develop secure national-level platforms for battery data exchange. Participation in EU Battery Passport initiatives (mandated by EU 2023/1542) and partnerships with Nordic repurposers or OEMs could accelerate development.

Fire Safety and Risk Mitigation Systems

The Estonian Rescue Board and technical regulators have highlighted the lack of testing, locally validated fire suppression systems and room requirements for second-life battery installations. In Sweden and Norway, fire safety is tightly integrated with second-life systems, including the use of automatic fire suppression, thermal monitoring, and early fault detection. Fire safety solutions from the Nordics (e.g., enclosure design, sensor arrays) could be adapted and tested in Estonian conditions. Joint fire risk simulations and pilot installations could serve as a testing ground for localized standards in collaboration with the Estonian Rescue Board.

Repurposing and Refurbishment Facilities

Estonia currently lacks industrial-scale facilities or companies specializing in disassembly, remanufacturing, or reconfiguration of EV battery packs. Nordic countries have small- to mid-scale repurposing firms that extract modules from packs, test them, and repackage for stationary use. Encouraging joint ventures or pilot production lines with Nordic firms could catalyze the development of local repurposing capacity. EU and national funding (e.g., Green Transition funds) could support early-stage investment in semi-automated repurposing centers.

Grid Integration and Digital Energy Platforms

Integration of second-life batteries into the grid (e.g., for frequency regulation or load shifting) requires advanced control systems and interoperability with Estonia’s grid management tools. Finland and Sweden have developed Virtual Power Plant (VPP) platforms and aggregation services integrating second-life batteries into energy markets. Estonia’s smart grid readiness and digital energy infrastructure are relatively strong, allowing for rapid adoption of Nordic VPP and aggregation models. Collaborations with Nordic VPP providers (e.g., Tibber, Fortum Spring) could be explored to adapt such services to the Estonian energy market.

Standards and Certification Procedures

There is currently no national certification pathway in Estonia for second-life batteries as energy storage products. In the Nordics, public agencies and standardization bodies (e.g., NEK[4], SEK[5]) are working to formalize second-life battery requirements and testing standards. Estonia can adopt or adapt Nordic technical standards and certification schemes (e.g., safety classifications, and testing protocols). Participation in CEN-CENELEC[6] and EU-wide standardization projects could ensure alignment with broader European practices.

Recommendations for Estonia

In brief, the repurposing of second-life EV-batteries could begin with pilot projects in collaboration with local municipalities, energy companies, and research institutions. This would allow stakeholders to test the feasibility and safety of using second-life batteries in stationary storage applications (e.g., in public buildings, residential microgrids, or small-scale renewable energy integration). The practice could also be supported through targeted public funding (e.g., climate adaptation or circular economy funds) and integration into smart city initiatives.

Establishing partnerships with Nordic companies already operating in this space (such as ECO STOR) could provide access to technical know-how and systems integration experience. Additionally, regional policy dialogue between Baltic and Nordic regulatory bodies could help align standards and clarify cross-border responsibilities for battery reuse and traceability, thus reducing administrative barriers to transferability.

The following list presents recommendations on how to foster the development of the technical and institutional ecosystem to implement such practice in Estonia:

1. Develop a National Regulatory Framework for Second-Life Battery Governance

A national task force or working group should be established—including ministries, the Rescue Board, the Consumer Protection Board, the Environment Agency, and technical universities—to clarify roles, define classification pathways (product vs. waste), and propose a regulatory sandbox for testing second-life battery deployments under supervised conditions.

2. Develop Pilot Projects and Risk-Mitigated Demonstrations

Government and academic institutions should co-develop pilot projects with industry to test repurposed batteries in controlled settings (e.g., municipal buildings, or rural grids). These should include fire suppression systems, data logging, and emergency training for responders to generate safety evidence and best practices relevant to Estonia.

3. Establish Testing and Refurbishment Capacity in Estonia

Public investment or PPP models should be explored to develop national battery testing labs (e.g., at TalTech), which could support battery diagnostics, SoH evaluation, and fire safety testing. Mobile testing units or partnerships with Nordic labs (e.g., RISE or IFE) can bridge short-term gaps.

4. Improve the Awareness on Topics of Producer Responsibility and Ownership Transfers

Legal Frameworks on Producer Responsibility and Ownership Transfers should be well communicated to different stakeholders, especially those dealing with second-life batteries and working in the repurposing business. Ownership, warranty, and liability frameworks must be clearly understood by all stakeholders when batteries transition from automotive to stationary use.

5. Adapt and Adopt Nordic and EU Standards

Estonia should adopt harmonized EU and Nordic standards (e.g., IEC[7], CEN-CENELEC) for repurposed battery testing, labelling, fire safety, and traceability. Participation in the EU Battery Passport implementation is critical for aligning with upcoming regulatory requirements and ensuring access to technical battery data.

6. Educate Installers, Inspectors, and Emergency Services

Training programs should be developed for technicians, building inspectors, and first responders to build practical capacity around second-life battery installation and incident response. Experiences from Nordic stakeholders in managing safety protocols can serve as a model curriculum.

7. Promote Cross-Border Knowledge Exchange and Consortia

Estonia should actively participate in Horizon Europe projects and Nordic-Baltic platforms focused on battery reuse and circular energy systems. These collaborations can accelerate knowledge transfer, standard development, and co-investment in shared infrastructure.

[1] RISE Research Institutes of Sweden is an independent, state-owned research institute, which offers unique expertise and over 130 testbeds and demonstration environments for future-proof technologies, products and services. Accessible at: https://www.ri.se/en/about-rise 27.5.2025

[2] IFE – a research institute for Energy Technology in Norway. More information accessible at: https://ife.no/en/about-ife/ 27.5.2025

[3] ECO STOR is the private Norwegian company providing energy storage solutions. More information accessible at: https://www.eco-stor.com/ 23.5.2025

[4] Norwegian Electrotechnical Committee (NEK) is an independent and neutral organisation promoting electrotechnical standardisation and the use of standards at the national, regional and international levels. Accessible at: Forsiden – Norsk Elektroteknisk Komite (NEK) 27.5.2025

[5] SEK Svensk Elstandard is responsible for standardization in Sweden in the field of electrotechnology. The organization also co-ordinates Swedish participation in European and international standardization work as a member of the IEC and CENELEC. Accessible at: https://elstandard.se/in-english 27.5.2025

[6] The European Electrotechnical Committee for Standardization is one of three European Standardization Organizations (together with CEN and ETSI) that have been officially recognized by the European Union and by the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) as being responsible for developing and defining voluntary standards at European level. Accessible at: https://www.cencenelec.eu/about-cenelec/ 27.5.2025

[7] International Electrotechnical Commission